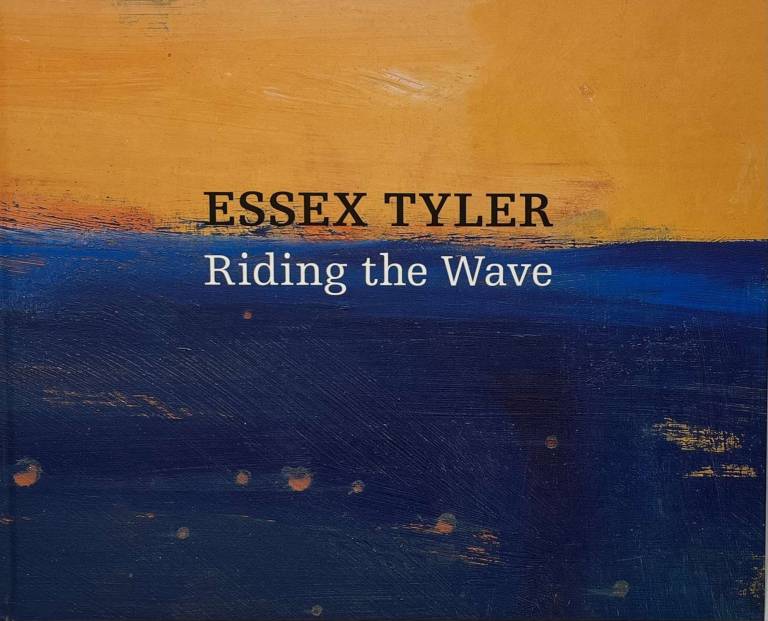

Essex Tyler

Of the four elements – water, fire, air and earth - water is

the vital force in Essex Tyler’s work. Not surprisingly, given that his

identity as a surfer, sailor and fisherman bleeds in to his art. As a painter,

Essex brings together big liquid skies, the irascible Atlantic Ocean and the

copper-stained cliffs of West Cornwall in landscapes that move one step beyond

his contemporaries in capturing a quiet intensity, a kind of brooding – but a

celebratory brooding. Heron-blue skies weigh heavy on golden rocks that are

bursting treasure chests – but this is not sweet earth. It spills out in rough

coughs against the incessant forced medicine of the Atlantic Ocean. Sometimes

the bronze of fiery earth leaks into the sky and stains it. Essex first

established himself as a potter, so he knows the clays and metals that stain

his paintings intimately. It is this translation of the physicality of clay

forms and their firing into painting that makes his canvases so unique and

powerful. Raku pots, veined with cobalt, want to burst open like ripe fruit.

The textures are smooth and burnished, with intricate cracks appearing by

chance, a metaphor for life.

“Painting is like surfing. You do not get anywhere before

you have mastered the basics – spot the best waves, paddle out using the rip

currents, take off at the point of maximum energy, bottom turn, tube ride, exit

with style.” But, of course, after that, spontaneous and sometimes

unintentional movements can produce poetry on the waveface. Essex uses oils,

acrylics, beeswax and marble dust. Colours, tones and textures are repeated

over and over to work as building blocks, so that improvisation becomes

possible. Paint is pushed and pulled around the canvas, leaving traces that are

tethers, tracks for the eye to follow upward, across, to finally rest on a

deceptively still object, a symbol of shelter not just at the heart of the

storm but also at the heart of the calm. For one of painting’s key purposes is

to provide shelter from the anaesthetising calm that is the pervasive blandness

produced by a mundane culture.

I’ve watched Essex surfing on big greasy green waves all

around the south coast of Cornwall, just under the big toe of the foot of

county dipped in the Atlantic turbine, setting up a crisp bottom turn, adopting

great posture, flexing low into outlandish re-entries, followed by rifling

moves all the way to the shoreline, everything linked and coordinated. And now,

this same string of events passes from head and heart to brush and canvas, with

paint as the medium rather than the green Atlantic Ocean. In each arena,

liquidity is key – flow, movement, acceleration and pause, timing and

placement.

-

Autumn Penwith Moorland

£ 750.00 -

Carn Galva

£ 750.00 -

Ding Dong from Lanyon Quoit

£ 475.00 -

Ginny Iden

£ 525.00 -

High Tide Sennen

£ 850.00 -

Ladydowns near Zennor

£ 600.00 -

Lichen Coast

£ 575.00 -

Nanquidno

£ 850.00 -

North Coast

£ 3,500.00 -

North Coast

£ 1,250.00 -

Orion’s Star

£ 2,500.00 -

Penwith Moorland

£ 1,250.00 -

Riding the Wave

£ 25.00 -

Scarlett Thread

£ 1,250.00 -

Sennen High Tide

£ 4,750.00 -

Winter Bowl

£ 375.00